Wushu Temples: Shaolin and Wudang

The association between religious temples in China and the martial arts is very rich and vibrant, but it may have more to do with legend and myth than history. With so many different schools of Wushu claiming rich and often contradictory histories, and it seems, such few reliable sources of documentation – it’s hard to say where truth lies.

I suppose that’s the case with oral traditions – how do you verify them? And secondly – how much does it really matter? What is the value of history over legend?

To a Western audience, the most famous temples of martial arts are Shaolin (also Sil Lum) and Wudang (also Wu Tang). Many films and television shows have been made about the temples and the monks who developed their skills there, and over time, a certain rivalry and methods of classification have developed between different schools.

There are many more temples, of course, and many more styles of martial arts in China, but for the purposes of this essay, we shall discuss Shaolin and Wudang, these temples have come to represent a binary of sorts, and the associations and differences between their martial arts.

I suppose that’s the case with oral traditions – how do you verify them? And secondly – how much does it really matter? What is the value of history over legend?

To a Western audience, the most famous temples of martial arts are Shaolin (also Sil Lum) and Wudang (also Wu Tang). Many films and television shows have been made about the temples and the monks who developed their skills there, and over time, a certain rivalry and methods of classification have developed between different schools.

There are many more temples, of course, and many more styles of martial arts in China, but for the purposes of this essay, we shall discuss Shaolin and Wudang, these temples have come to represent a binary of sorts, and the associations and differences between their martial arts.

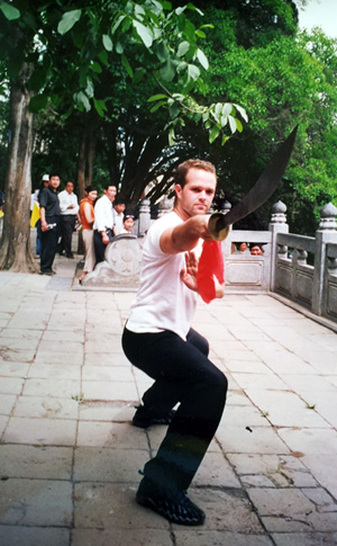

Chris at the Shaolin Temple, March 2001

Chris at the Shaolin Temple, March 2001

In broad terms, Shaolin Wushu or Kung Fu styles are regarded as ‘external’, in that they appear strong, quick and forceful, and the monks demonstrate great feats of physical strength.

Conversely, Wudang styles are regarded as ‘internal’ styles, and they focus more on meditative traditions and softer styles which could be considered more evasive, in some ways more complex and subtle, and more meditative in nature. Sometimes people say the essence of an ‘internal’ style is more on developing the condition of the practitioner, than it is on learning combat applications.

One might also use the terms: Shaolin Kung Fu or Wudang Tai Chi, which is a simple and broad way of implying difference between the styles.

Shaolin is a Buddhist temple, and Wudang is a Taoist temple. This leads to other associations too, in regards to weaponry – Buddhists are seen as more gentle, or at least unwilling to kill, therefore they are known as being strong fighters with the staff or cudgel – a blunt wooden weapon which is not used with the intention to kill, but also may be used for crowd control, or just as a tool in general.

Conversely, the weapon that is most celebrated at Wudang is the sword, jian, which is considered to be a gentlemanly or scholarly choice – it requires grace and subtlety to master – but are they less concerned with the morality of killing people at Wudang? It could all be academic, because frankly they do practice with the sword at Shaolin, just as they practice with the cudgel and a range of other weapons at Wudang.

If we are to discuss in more immediate terms what martial arts are practiced at the temples today, and how the styles differ – the lines are rather blurred. At Wudang, they practice Bajiquan – widely considered an internal style of martial arts, but they also practice Baji at Shaolin (the description in the link acknowledges that Baji was not born of Shaolin, although it has become an important style at the temple since then). You can see as well in these two links, that the Wudang demonstration does not appear softer than the Shaolin style. Of course, comparing two or three practitioners cannot give an accurate representation of the styles themselves; to take a scientific approach you could say it does not provide any kind of statistical significance; the sample size is too small, too narrow.

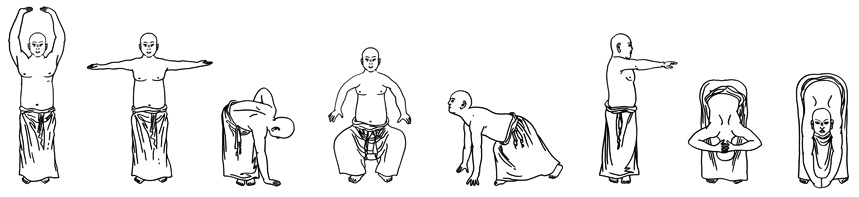

Also, the ancient Qigong practice of Ba Duan Jin is practiced at both temples, by practitioners from both lineages, even though it is not thought to be the case that it was born at either temple.

Having said all this, if you describe a Shaolin practitioner’s art as external, they will be quick to point out all the internal training they undertake and master, and likewise if you describe a Wudang practitioner’s art as only soft, they will be quick to point out the effective combat applications of their style and their vigorous and demanding physical training methods.

Of course there are some styles that are thought to be essential to Shaolin especially in terms of historical significance, such as Luohan, the method of the enlightened priest; but even then it can hardly be said that the techniques and attitudes to be found here are not also shared across other styles.

So it appears to be the case is that there are not really any distinct or exclusive Shaolin or Wudang styles. At the Shaolin temple, they practice Hongquan, Tong Beiquan, and other styles, all of which are also practiced in other parts of China, by a range of people. Any basic Shaolin training routines you are likely to see, that do not also belong to another lineage from somewhere else, will incorporate a range of techniques that are similar or related to any number of these other styles, and so common themes and movement patterns begin to appear, and the modern Shaolin style appears to have a certain flavour to it, but it’s difficult to nail down a unique Shaolin style of martial arts that does not also have a strong historical presence in another part of China.

Likewise, Wudang is known primarily for the practice of the three most popular internal styles of martial arts: Tai Chi Chuan (Taijiquan), Xing-Yi, and Ba Gua. It is frequently argued that none of these styles originated at Wudang – though it also needs to be said that there are two primary accounts for the historical development of Tai Chi Chuan – one lineage claims that it originated in the Chen village, which is close to Shaolin, and the other claims it originated at Wudang, some several generations earlier.

Again, there appears to be a regrettably limited body of evidence to support either case.

Conversely, Wudang styles are regarded as ‘internal’ styles, and they focus more on meditative traditions and softer styles which could be considered more evasive, in some ways more complex and subtle, and more meditative in nature. Sometimes people say the essence of an ‘internal’ style is more on developing the condition of the practitioner, than it is on learning combat applications.

One might also use the terms: Shaolin Kung Fu or Wudang Tai Chi, which is a simple and broad way of implying difference between the styles.

Shaolin is a Buddhist temple, and Wudang is a Taoist temple. This leads to other associations too, in regards to weaponry – Buddhists are seen as more gentle, or at least unwilling to kill, therefore they are known as being strong fighters with the staff or cudgel – a blunt wooden weapon which is not used with the intention to kill, but also may be used for crowd control, or just as a tool in general.

Conversely, the weapon that is most celebrated at Wudang is the sword, jian, which is considered to be a gentlemanly or scholarly choice – it requires grace and subtlety to master – but are they less concerned with the morality of killing people at Wudang? It could all be academic, because frankly they do practice with the sword at Shaolin, just as they practice with the cudgel and a range of other weapons at Wudang.

If we are to discuss in more immediate terms what martial arts are practiced at the temples today, and how the styles differ – the lines are rather blurred. At Wudang, they practice Bajiquan – widely considered an internal style of martial arts, but they also practice Baji at Shaolin (the description in the link acknowledges that Baji was not born of Shaolin, although it has become an important style at the temple since then). You can see as well in these two links, that the Wudang demonstration does not appear softer than the Shaolin style. Of course, comparing two or three practitioners cannot give an accurate representation of the styles themselves; to take a scientific approach you could say it does not provide any kind of statistical significance; the sample size is too small, too narrow.

Also, the ancient Qigong practice of Ba Duan Jin is practiced at both temples, by practitioners from both lineages, even though it is not thought to be the case that it was born at either temple.

Having said all this, if you describe a Shaolin practitioner’s art as external, they will be quick to point out all the internal training they undertake and master, and likewise if you describe a Wudang practitioner’s art as only soft, they will be quick to point out the effective combat applications of their style and their vigorous and demanding physical training methods.

Of course there are some styles that are thought to be essential to Shaolin especially in terms of historical significance, such as Luohan, the method of the enlightened priest; but even then it can hardly be said that the techniques and attitudes to be found here are not also shared across other styles.

So it appears to be the case is that there are not really any distinct or exclusive Shaolin or Wudang styles. At the Shaolin temple, they practice Hongquan, Tong Beiquan, and other styles, all of which are also practiced in other parts of China, by a range of people. Any basic Shaolin training routines you are likely to see, that do not also belong to another lineage from somewhere else, will incorporate a range of techniques that are similar or related to any number of these other styles, and so common themes and movement patterns begin to appear, and the modern Shaolin style appears to have a certain flavour to it, but it’s difficult to nail down a unique Shaolin style of martial arts that does not also have a strong historical presence in another part of China.

Likewise, Wudang is known primarily for the practice of the three most popular internal styles of martial arts: Tai Chi Chuan (Taijiquan), Xing-Yi, and Ba Gua. It is frequently argued that none of these styles originated at Wudang – though it also needs to be said that there are two primary accounts for the historical development of Tai Chi Chuan – one lineage claims that it originated in the Chen village, which is close to Shaolin, and the other claims it originated at Wudang, some several generations earlier.

Again, there appears to be a regrettably limited body of evidence to support either case.

The Yi Jin Jing is an ancient system of Qigong, named the Muscle Changing Classic, because practice is said to give you powerful, wiry muscles and strong bones. It is thought to be fifteen-hundred years old, created by the founder of Shaolin martial arts, Bodhidharma, and the fact that it is not from Wudang does not mean that it is not a powerful internal practice.

So what’s the point of all this? It sounds vague, I know, as if nobody knows what’s really going on. Personally, I enjoy the romance and mystery surrounding the temples and the history of martial arts in China and other countries, but it can be frustrating when people who practice vastly different styles argue over who possesses the secret to real, authentic Shaolin arts, and when people argue over history as if they really can know for certain – well it is a rather long and old argument.

And when one martial artist says to another “oh, your style came from mine” – it can be condescending, and nobody enjoys that. But is the original automatically better, or conversely has development and growth over time done the style well? And who can say which is the best martial art? That argument too, has yet to be resolved.

Maybe it simply comes down to impressions, attitudes, and ways of delineating between the styles:

If someone tells you they practice Shaolin, there are many possible implications. It is a Buddhist temple; their arts are known for being strong, athletic, and powerful – and they are famous for the use of the cudgel. There are also a great number of southern Chinese styles of martial arts who trace their lineage back to Shaolin including White Crane, Hung Gar, Choy Lay Fut, and Wing Chun, which was taught to Bruce Lee when he was young.

Wudang is a Taoist temple, and their arts are known for being subtle, complex and meditative – and their practitioners are famous for their skill with the sword. But these are hardly limiting factors, as so many skilled martial artists from Wudang can rival Shaolin monks in feats of strength, and Shaolin internal practices seem to be just as subtle and complex as those from Wudang.

And many styles of martial arts these days claim to have their origins in a temple, one of these or many others, but who can really tell? Some documentation exists, but far less than would be useful or provide us with much in the way of reliable conclusions.

This much it seems is true: the martial arts are more highly regarded and popularly practiced these days than ever before. Their pursuit is considered virtuous and neither base nor thuggish, and there is much to be learned about the mind, and much strength of character to be gained through training and exercising the body.

Something I value in particular about the association between the martial arts and monastic institutions, is the emphasis such association places upon ethics, morality, and restraint – or the correct use of power in a responsible manner. Martial arts should be employed only in service of the needy, to protect and educate an individual and the people, rather than for the oppression of the weak or the pursuit of selfish agendas.

So what’s the point of all this? It sounds vague, I know, as if nobody knows what’s really going on. Personally, I enjoy the romance and mystery surrounding the temples and the history of martial arts in China and other countries, but it can be frustrating when people who practice vastly different styles argue over who possesses the secret to real, authentic Shaolin arts, and when people argue over history as if they really can know for certain – well it is a rather long and old argument.

And when one martial artist says to another “oh, your style came from mine” – it can be condescending, and nobody enjoys that. But is the original automatically better, or conversely has development and growth over time done the style well? And who can say which is the best martial art? That argument too, has yet to be resolved.

Maybe it simply comes down to impressions, attitudes, and ways of delineating between the styles:

If someone tells you they practice Shaolin, there are many possible implications. It is a Buddhist temple; their arts are known for being strong, athletic, and powerful – and they are famous for the use of the cudgel. There are also a great number of southern Chinese styles of martial arts who trace their lineage back to Shaolin including White Crane, Hung Gar, Choy Lay Fut, and Wing Chun, which was taught to Bruce Lee when he was young.

Wudang is a Taoist temple, and their arts are known for being subtle, complex and meditative – and their practitioners are famous for their skill with the sword. But these are hardly limiting factors, as so many skilled martial artists from Wudang can rival Shaolin monks in feats of strength, and Shaolin internal practices seem to be just as subtle and complex as those from Wudang.

And many styles of martial arts these days claim to have their origins in a temple, one of these or many others, but who can really tell? Some documentation exists, but far less than would be useful or provide us with much in the way of reliable conclusions.

This much it seems is true: the martial arts are more highly regarded and popularly practiced these days than ever before. Their pursuit is considered virtuous and neither base nor thuggish, and there is much to be learned about the mind, and much strength of character to be gained through training and exercising the body.

Something I value in particular about the association between the martial arts and monastic institutions, is the emphasis such association places upon ethics, morality, and restraint – or the correct use of power in a responsible manner. Martial arts should be employed only in service of the needy, to protect and educate an individual and the people, rather than for the oppression of the weak or the pursuit of selfish agendas.